Discovering Suite Française by Irène Némirovsky was such a gift. I don’t remember how I became aware of this book, but there was no waiting line for this 2006 edition (Sandra Smith, translator) at the library. I was immediately pulled into the narrative which coincided with the narrative of the events in Ukraine. People on the road—walking, driving, hurrying along, carrying what they could. Not sure when, or if, they’d go home again. Air raid sirens in the background. No, not near Kyiv, but near Paris. Not late February, 2022, but early June, 1940.

If the setting wasn’t enough, then the exquisite prose kept my eyes on the page and in my mind’s eyes I saw the beauty of the French countryside juxtaposed against the ugliness of war.

But it wasn’t the setting, the prose, or the perceptively-drawn characters that held my attention to the very end. . . that made me read with careful deliberation. It wasn’t even the narrative—of love, hate, insecurity and surrender—between conquerors and the conquered, between rich and poor, between family members and couples—that kept my reading slow and intent.

No, it was the story behind the story that continues to reverberate within me. Irène Némirovsky died in Auschwitz in the summer of 1942 and this novel, Suite Française, was unfinished. The appendix shares her notes and plans to make the 300-page manuscript into a 1000-page tome. The appendix also shares letters written on her behalf to rescue her from the Nazi clutches.

|

| Public Domain from 1928 |

Born in Kiev (Kyiv) in 1903, Némirovsky had a lonely—although lavish—childhood. She spent much of it in Moscow and St. Petersburg, fleeing after the 1917 Revolution, and ended up in France. Her literary success came early with the release of David Golder in 1929 and made into a hit movie in 1931. She was abruptly arrested in July, 1942 and died soon after. Her husband tried to help find her but also died in a camp later that year. Their two young daughters survived only through the help of friends.

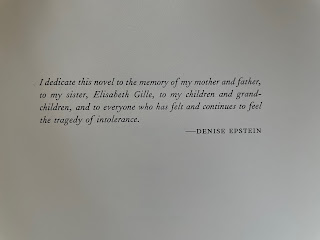

The inscription in the 2006 translation by Sandra Smith, written by the surviving daughter, Denise Epstein, reads:

The tragedy of intolerance continues to stalk our times. But secrets lose their power in the light and books like this shine light.

There's another, older and deeper, reason this book resonated with me. As a child, my dad once shared memories of being a Luftwaffe officer in occupied France. I don't remember where, but it was a happy memory for him of a place with endless bottles of cognac and burgundy. I was just a kid and the memory's dim. Yet, this novel highlighted that dinner conversation from my childhood. What ominous times.

No comments:

Post a Comment